Here’s something that surprises almost everyone the first time they learn it: you don’t “steer” an airplane the same way you steer a car.

In a car, you turn the steering wheel and the front wheels point in the new direction. The car follows. Simple and linear. In an airplane, you move a control wheel (or stick, depending on the design) and three different control surfaces deflect in different directions, creating aerodynamic forces that change the airplane’s orientation in three-dimensional space.

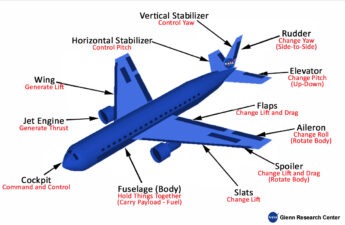

It’s not harder. It’s just different. And once you understand what each control does and why, it starts to feel natural. In Anatomy of an Airplane, we identified the five main components of an airplane. Now let’s get specific about the control surfaces — the movable parts that let a pilot actually fly the thing.

The Three Axes of Rotation

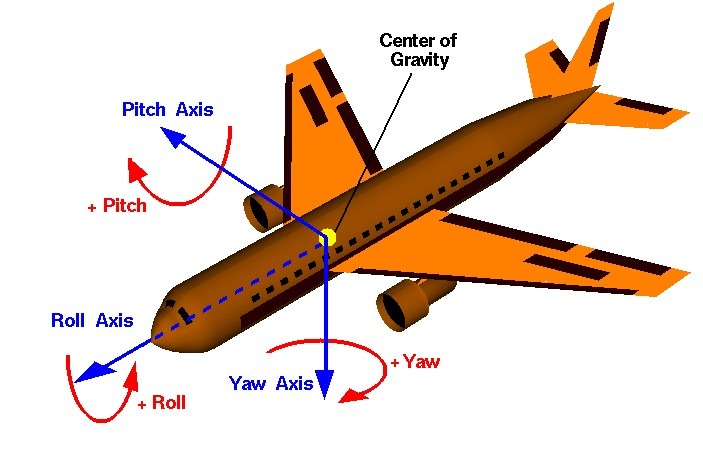

Before we talk about controls, we need to establish the framework. An airplane in flight can rotate around three axes, all passing through the center of gravity.

The longitudinal axis runs from the nose to the tail. Roll the airplane left or right, and you’re rotating around this axis. Think of a barbecue spit.

The lateral axis (also called the transverse axis) runs from wingtip to wingtip. Pitch the nose up or down, and you’re rotating around this axis.

The vertical axis runs straight up and down through the center of the airplane. Yaw the nose left or right, and you’re rotating around this axis.

Every movement an airplane makes is some combination of rotation around these three axes. The genius of the Wright brothers wasn’t just building a powered flying machine, it was figuring out how to control rotation around all three axes simultaneously.

Primary Flight Controls: The Big Three

Flight controls can be divided into two categories: primary and secondary.

The primary flight controls are essential to safe flight. You can’t fly without them. They are the ailerons, the elevator (or stabilator), and the rudder.

Each one controls rotation around a specific axis.

Ailerons: Roll Control

Ailerons sit on the outboard trailing edge of each wing. They control rotation around the longitudinal axis (roll).

Here’s how they work: when you turn the control wheel (or move the stick) to the right, the right aileron deflects upward and the left aileron deflects downward. They always move in opposite directions.

The wing with the downward-deflected aileron generates more lift and that wing rises. The wing with the upward-deflected aileron generates less lift and that wing drops. The airplane banks to the right.

But there’s a catch, and it’s called adverse yaw.

The downward-deflected aileron doesn’t just generate more lift, it also generates more drag. That extra drag slows that wing down slightly, causing the nose to yaw in the opposite direction of the desired turn. You roll right, but the nose wants to yaw left. It’s subtle at high speeds but pronounced at low speeds and high angles of attack.

Pilots compensate for adverse yaw by coordinating aileron input with rudder input. This is called coordinated flight, and it’s one of the first skills student pilots practice.

Some aircraft use differential ailerons to reduce adverse yaw. The upward-moving aileron deflects farther than the downward-moving aileron, creating extra parasite drag on the rising wing to balance out the induced drag on the descending wing.

Elevator: Pitch Control

The elevator sits on the trailing edge of the horizontal stabilizer and controls rotation around the lateral axis (pitch).

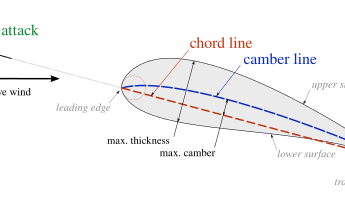

Pull back on the yoke or stick, and the elevator deflects upward. This changes the camber of the horizontal stabilizer, creating a downward aerodynamic force. The tail gets pushed down, the nose pitches up.

Push forward, and the elevator deflects downward, creating an upward force that pushes the tail up and the nose down.

The elevator is your primary tool for controlling airspeed and altitude. Want to climb? Pitch up and add power. Want to descend? Pitch down and reduce power. The elevator makes it happen.

Some aircraft replace the separate horizontal stabilizer and elevator with a stabilator. This is a single-piece horizontal tail that pivots as a unit around a central hinge point. It’s more effective than a conventional elevator but requires careful engineering to avoid over-sensitivity. Many stabilators include an anti-servo tab on the trailing edge that moves in the same direction as the stabilator itself, increasing control feel and preventing over-control.

Rudder: Yaw Control

The rudder is hinged to the trailing edge of the vertical stabilizer and controls rotation around the vertical axis (yaw).

Push the left rudder pedal, and the rudder deflects to the left. This creates a sideways aerodynamic force that pushes the tail to the right and yaws the nose to the left. Push the right pedal, the nose yaws right.

The rudder is not used to turn the airplane. That’s a common misconception. Turns are made by banking the airplane with the ailerons, which tilts the lift vector and changes the direction of flight. The rudder’s job is to coordinate the turn; that is to keep the nose pointed in the direction the airplane is actually moving.

Coordinated Flight: Making the Controls Work Together

Here’s the reality: you almost never use just one control at a time.

When you want to turn left, you roll left with the ailerons. But if you don’t add left rudder, adverse yaw will cause the nose to swing right. The airplane will be in a skidding turn — sliding sideways through the air. An uncoordinated turn is uncomfortable for your passengers, aerodynamically inefficient, and can even be dangerous in certain situations.

A coordinated turn is one where the ailerons and rudder work in harmony. The nose points exactly where the airplane is going. The ball in the turn coordinator stays centered and the flight feels smooth.

This is the skill that separates a pilot from someone who can make an airplane go up and down. It takes practice. Lots of it. But once you develop the muscle memory, it becomes instinctive.

Trim Tabs: Flying Hands-Off

A trim tab is a small hinged surface on the trailing edge of a primary control surface — usually the elevator, sometimes the rudder or ailerons.

Here’s the clever part: when you deflect a trim tab, it creates an aerodynamic force that moves the main control surface in the opposite direction. Move the elevator trim tab down, and it pushes the elevator up, which pitches the nose down.

The purpose of trim is to relieve control pressure. Without trim, you’d have to hold constant pressure on the yoke to maintain a given pitch attitude. Trim lets you set the desired pitch and let go so the airplane stays there on its own.

Flaps: More Lift, More Drag, Slower Flight

We covered flaps briefly in The Anatomy of an Airplane. Flaps increase the camber of the wing, which increases both lift and drag. Extending flaps allows the airplane to fly slower without stalling, which is exactly what you want during takeoff and landing.

Putting It All Together

Here’s what actually happens when a pilot makes a left turn in a Cessna 172:

- Aileron input: Turn the yoke left. The left aileron goes up and the right aileron goes down. The airplane begins to roll left.

- Rudder coordination: Add a bit of left rudder to counteract adverse yaw.

- Elevator back pressure: As the airplane banks, part of the lift vector tilts horizontally. To maintain altitude, pull back slightly on the yoke.

- Roll out: Reverse the aileron and rudder inputs to stop the turn and return to wings-level flight.

- Trim: Adjust trim to relieve control pressure once established on the new heading.

It sounds complicated when written out step by step. But after a few hours of practice, it becomes as natural as walking, driving, or riding a bike.

Why This Matters Before You Solo

Understanding how the controls work doesn’t just help you pass your written exam. It helps you understand what the airplane is doing and why. When your instructor says “more right rudder,” you’ll know it’s because the propeller torque is yawing you left and you need to counteract it. The Wright brothers’ breakthrough wasn’t just powered flight. It was controlled powered flight. They figured out how to manage pitch, roll, and yaw simultaneously — something no one had done before. Every time you take the controls, you’re building on their work.

Want to see how much you remember from this post? Here’s a quiz!