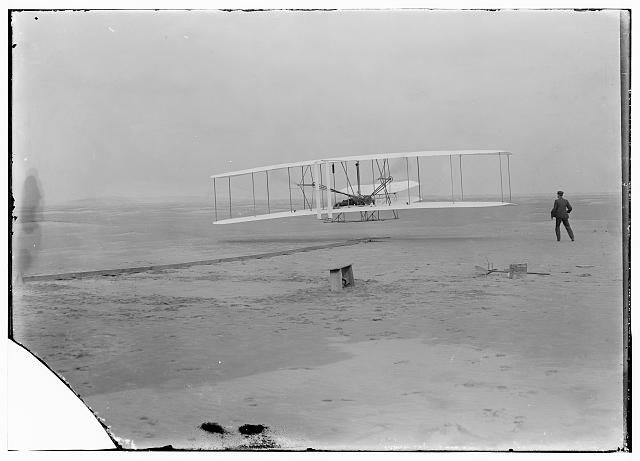

On the morning of December 17, 1903, a man named John T. Daniels crouched behind a camera on a cold, windy beach in North Carolina. He had never taken a photograph in his life. Wilbur Wright handed him a rubber bulb and told him to squeeze it if anything interesting happens.

Something interesting happened. Daniels squeezed. And the resulting image, which was grainy and slightly tilted, captured the exact moment a machine carrying a human being left the ground under its own power for the first time in history.

The flight lasted 12 seconds. It flew a distance shorter than the wingspan of a modern 747. And yet, every commercial flight, every military jet, every crop duster, air ambulance, and private plane traces a direct line back to that frozen moment on the Outer Banks.

If you’ve ever wondered how something that heavy actually stays in the sky, you’re asking exactly the right question. Let’s answer it.

The Big Idea: Four Forces Are Always Fighting

Whether you’re looking at the Wright Flyer or a Boeing 787 Dreamliner, every airplane that has ever flown is caught in a constant tug-of-war between four forces. Understand those four forces, and you understand flight.

They are lift, weight, thrust, and drag.

Think of them as two pairs of opposites. Lift pushes the airplane up; weight (gravity) pulls it down. Thrust pushes the airplane forward; drag (air resistance) pushes back against it. When an airplane is cruising smoothly at altitude, all four of these forces are perfectly balanced. When a pilot wants to climb, they tip the balance toward lift. To slow down, they let drag win for a moment. The entire art of flying is really just the art of managing these four forces in real time.

NASA’s Beginner’s Guide to Aeronautics has a great visual breakdown of this balance if you want to dig deeper.

So How Does Lift Actually Work?

Here’s where it gets interesting and where a lot of people have been taught something that isn’t quite right.

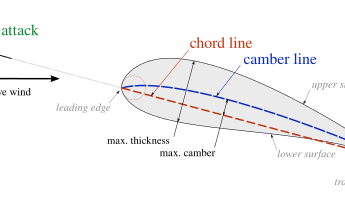

You’ve probably heard the “equal transit time” explanation: air traveling over the curved top of a wing has farther to go than air traveling under the flatter bottom, so it has to speed up to “meet” the other air at the back of the wing. Faster air means lower pressure (Bernoulli’s principle), and lower pressure on the top of the wing causes the higher pressure on the bottom to push the wing up.

But that explanation is incomplete. Air going over the top of a wing does not need to meet the air from the bottom at the trailing edge. That’s a myth taught to simplify it. In reality, the air on top moves much faster than the equal-transit theory would ever predict.

The real picture involves both Bernoulli’s principle and Newton’s third law, working together. A wing is shaped and angled so that it redirects airflow. As air flows over the curved upper surface, it accelerates and clings to the wing’s shape. The wing essentially grabs the air and deflects it downward. By Newton’s third law (every action has an equal and opposite reaction), pushing air down means the air pushes the wing up. At the same time, that accelerating air above the wing creates a zone of lower pressure, which also contributes to the upward pull.

Lift is the combined result of both effects (and in reality is even more complicated than this). These effects are what keeps you in the sky.

The Angle of Attack: The Most Important Concept in Aviation

The angle at which a wing meets the oncoming air is called the angle of attack. Tilt the wing’s leading edge up a bit more, and you generate more lift — up to a point. Tilt it too far, and the smooth airflow over the top of the wing breaks apart into chaotic turbulence. Lift collapses almost instantly. This is called a stall, and it’s one of the very first things every pilot learns to recognize and recover from.

Here’s the part that non-pilots are not familiar with: in aviation, a stall has absolutely nothing to do with the engine. You can stall at full throttle. You can stall while climbing, descending, or in the middle of a turn. The stall is purely about angle of attack. Push the wing too far past its limits and the air simply can’t follow the curve anymore.

This is why pilots spend so much time on stall recognition and recovery. It’s not just a checkbox exercise. It’s a direct confrontation with one of flight’s most fundamental limitations.

Drag: The Necessary Evil You Can’t Avoid

Drag is the force that works against forward motion, and it comes in two main flavors.

Parasite drag is caused by the airplane just being in the way of the air. The fuselage, landing gear, antennas, and every surface that isn’t a wing all produce resistance simply by existing. The faster you go, the worse parasite drag gets. This is why streamlining of the plane matters.

Induced drag is a byproduct of lift itself. Every time a wing generates lift, it also generates drag as a side effect. The counterintuitive part of induced drag is that it is worst at slow speeds. When you’re flying slowly, the wing has to work much harder to generate enough lift, which means a higher angle of attack. And the harder the wing works, the more induced drag it creates.

These two types of drag actually pull in opposite directions as you change speed: parasite drag gets worse as you speed up, induced drag gets worse as you slow down. Where they meet in the middle is the most efficient speed for a given aircraft.

Thrust: Moving Fast Enough to Fly

Thrust is simply the force that moves the airplane forward. Without it, there’s no airflow over the wings, and without airflow, there’s no lift. This is the fundamental reason a fixed-wing airplane can’t hover like a helicopter. The wings need to be moving through the air to work.

Most small training aircraft use a piston engine turning a propeller. The propeller itself is a fascinating application of the same physics: each propeller blade is shaped like a wing, generates its own “lift” (in this case, directed forward as thrust), and is subject to the exact same aerodynamic principles. A propeller is really just a pair of spinning wings pointed the wrong direction.

Why You Need to Know This Before You Ever Touch a Cockpit

You can memorize every checklist and radio call in existence, but if you don’t understand why a wing works you’ll never fully understand what’s happening when something starts going wrong. Procedures tell you what to do. Physics tells you why.

The Wright brothers didn’t build their machine and hope for the best. They built a wind tunnel. They tested dozens of airfoil shapes. They ran the numbers. They figured out that the real unsolved problem in flight wasn’t power, it was control. And on a December morning with a 27 mph headwind and a borrowed camera, they proved they’d figured it out.

Over a hundred years later, watching a 400-ton aircraft lift off a runway and disappear into the clouds still feels a little like magic.

Ready to see how much you remember from this post? Here’s a fun quiz!