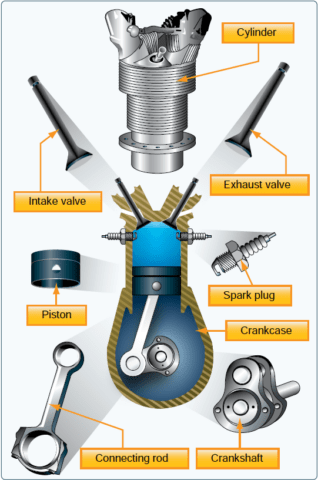

The first time you walk up to a Cessna 172 and peer into the cowling during preflight, you’re looking at an aircraft engine with roughly 180 horsepower worth of carefully balanced mechanical complexity. Cylinders, pistons, a crankshaft, spark plugs, magnetos, a carburetor or fuel injection system, oil lines, cooling baffles, and a propeller bolted to the front.

It’s a lot. And yet the basic principle is almost absurdly simple: burn fuel, push a piston, turn a shaft, spin a propeller.

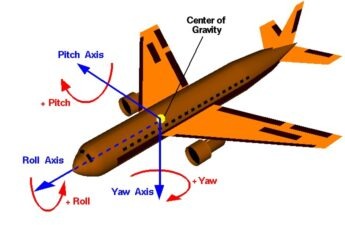

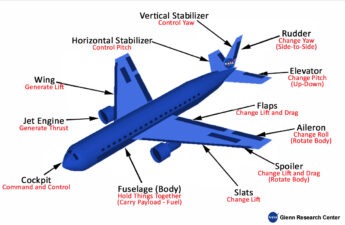

Everything else (the magnetos, the mixture control, the oil system, the ignition check before takeoff) exists to make that simple process reliable, efficient, and safe. In the post on flight controls, we covered how flight controls let you maneuver the airplane. Now let’s talk about what actually makes it move.

The Four-Stroke Cycle: How Pistons Turn Fuel Into Power

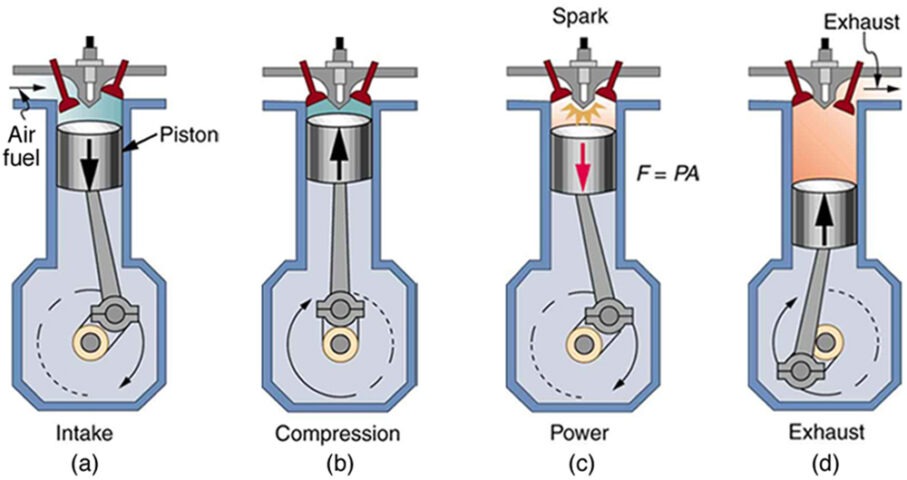

Most training aircraft use four-stroke piston engines. The term “four-stroke” refers to the four distinct movements of the piston required to complete one power cycle.

Here’s what happens inside a single cylinder:

1. Intake Stroke

The piston moves downward in the cylinder and the intake valve opens. The downward motion creates a vacuum that sucks a mixture of fuel and air into the cylinder from the carburetor or fuel injection system. At the bottom of the stroke, the cylinder is full of fuel-air mixture at roughly atmospheric pressure.

2. Compression Stroke

Both valves close. The piston moves back upward, compressing the fuel-air mixture into a much smaller space. Compression heats the mixture and makes it far more explosive when ignited. A typical compression ratio for a general aviation engine is around 8:1 or 9:1. In other words, the mixture is squeezed down to one-eighth or one-ninth of its original volume.

3. Power Stroke

Just before the piston reaches the top of the compression stroke, the spark plugs fire. The fuel-air mixture ignites and burns rapidly. Note that it is not an explosion, but a very fast, controlled burn. The resulting pressure spike drives the piston downward with tremendous force. This is the only stroke that actually produces power. The other three strokes are just setting up for this one moment.

4. Exhaust Stroke

The exhaust valve opens. The piston moves back upward, pushing the burned gases out of the cylinder and into the exhaust system. At the top of the exhaust stroke, the cycle starts over.

The whole process happens incredibly fast. At 2,400 RPM, which is a typical cruise setting in a small aircraft, each cylinder completes 1,200 full cycles per minute. That’s 20 cycles per second, per cylinder.

Why Four Cylinders (Usually)

Most training aircraft like the Cessna 172, Piper Cherokee, and Diamond DA40 use four-cylinder engines. Some use six. A few high-performance singles have eight.

The cylinders don’t all fire at the same time. They fire in a specific sequence designed to keep the engine running smoothly. In a four-cylinder engine, the firing order is typically 1-3-2-4. This means that at any given moment, one cylinder is on its power stroke, one is on compression, one is on intake, and one is on exhaust. The result is continuous, smooth power delivery to the propeller.

The most common configuration is the horizontally opposed engine — flat engines with cylinders arranged in two banks on opposite sides of the crankshaft. Lycoming and Continental are the two dominant manufacturers. The Lycoming O-320, for example, produces 150 to 160 horsepower and powers thousands of Cessna 172s.

The Magneto: Independent Ignition

Here’s something that surprises a lot of people: your airplane’s engine doesn’t need the battery or electrical system to keep running. It has its own self-contained ignition system called the magneto.

A magneto is a small electrical generator driven by the engine. It uses a spinning permanent magnet to generate high-voltage electricity, which is then sent to the spark plugs. As long as the engine is turning, the magneto is generating spark.

Every certificated aircraft engine has two magnetos acting as completely independent systems, each firing one spark plug in each cylinder. This is called dual ignition, and it serves two purposes:

- Redundancy. If one magneto fails, the other keeps the engine running. You’ll lose a little bit of power, but the engine won’t quit.

- Better combustion. Two spark plugs igniting the fuel-air mixture from two different locations burns the fuel more completely and efficiently, producing slightly more power.

During the pretakeoff runup, pilots check both magnetos by switching from BOTH to RIGHT, noting the RPM drop (typically 50 to 150 RPM), then switching to LEFT and noting the drop again. If the RPM drop is too large, if there’s a significant difference between the two magnetos, or if there is no difference at all, something is wrong.

The Carburetor: Mixing Fuel and Air

The carburetor’s job is simple: mix fuel and air in the correct ratio and deliver that mixture to the cylinders.

The most common type in light aircraft is the float-type carburetor. Air enters and flows through a narrow section called a venturi, which speeds up the airflow and lowers its pressure (Bernoulli’s principle strikes again). The low-pressure zone sucks fuel from a reservoir into the airstream, where it mixes with the air. The mixture then flows to the cylinders.

The throttle controls how much fuel-air mixture reaches the engine. The mixture control adjusts the fuel-to-air ratio. At sea level, the ideal ratio is about 15 parts air to 1 part fuel by weight. But as you climb, the air gets thinner. If you don’t adjust the mixture, the engine runs too rich (too much fuel for the available air). Leaning the mixture at altitude is standard practice.

The carburetor has one major weakness: carburetor ice. When air flows through the venturi it cools down, sometimes by 60°F or more. If there’s moisture in the air, that cooling can cause ice to form inside the carburetor, restricting airflow and choking the engine. Carburetor ice can form even when the outside air temperature is well above freezing. In humid conditions ice can form as high as 70°F.

The solution is carburetor heat. Pull the carb heat control, and you redirect warm air from around the exhaust manifold into the carburetor. The warm air melts any ice and prevents more from forming. You’ll see a slight RPM drop when you apply carb heat (because warm air is less dense), but that’s normal.

The Propeller: Turning Power Into Thrust

The propeller is the final link in the powerplant chain. The engine turns the crankshaft. The crankshaft turns the propeller. The propeller generates thrust.

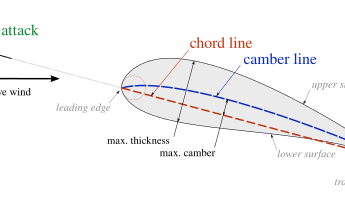

As we covered in the post on why airplanes fly, a propeller is really just a rotating wing. Each blade has an airfoil cross-section. As the blade moves through the air it generates lift just like a wing, but because the blade is moving forward, that “lift” is directed forward as thrust.

The pitch of a propeller blade is the angle between the blade and the plane of rotation. More pitch means the blade takes a bigger “bite” of air with each revolution.

The simplest propellers are “fixed-pitch”. The pitch is set at the factory and doesn’t change. These are cheap, reliable, and common on trainers. But they’re inefficient. A fixed-pitch propeller optimized for takeoff and climb will be inefficient at cruise.

Constant-speed propellers solve this problem. They use a governor mechanism to automatically adjust blade pitch to maintain a constant RPM, regardless of airspeed or power setting. At takeoff, you set high RPM (low pitch). At cruise, you reduce RPM (increase pitch). Constant-speed propellers are more complex and expensive, but they make a huge difference in performance and fuel efficiency.

Oil: The Lifeblood of the Engine

The engine oil system does far more than just lubricate moving parts. It also:

- Cools internal components by carrying heat away from hot spots

- Seals the gaps between piston rings and cylinder walls

- Cleans by suspending metal particles and combustion byproducts

- Protects against corrosion

Checking the oil before every flight isn’t optional. Low oil pressure in flight is an emergency. Running out of oil will destroy the engine in minutes. The oil temperature and oil pressure gauges in the cockpit give you real-time feedback on the health of the lubrication system.

Putting It All Together: The Engine Runup

Before every takeoff, pilots perform an engine runup. This is a systematic check of every critical engine system:

- Magnetos: Check each magneto individually and verify the RPM drop is within limits.

- Engine instruments: Oil pressure, oil temperature, cylinder head temperature, fuel flow, all in the green.

- Carburetor heat: Apply it and verify RPM drops slightly.

- Engine idle: Pull throttle to idle to verify the engine still runs, then turn off carburetor heat.

If anything doesn’t check out, you don’t go. The runup can sometimes feel like a formality, but it’s the last line of defense between you and an engine failure on takeoff.

Why This Matters Before You Solo

Understanding how the engine works doesn’t just help you pass your written exam. It helps you recognize when something is going wrong. When the engine starts running rough at altitude and you haven’t leaned the mixture, you’ll know the spark plugs are fouling from too much fuel. When you pull carb heat and the RPM rises instead of dropping, you’ll know you just melted ice that was choking the engine. The Wright brothers built their own engine because no one else made one light enough and powerful enough for flight. They hand-carved the propeller blades. They calculated the pitch by trial and error. Today’s engines are far more sophisticated. But the fundamentals haven’t changed. Burn fuel. Push a piston. Turn a shaft.

Ready to see how much you remember from this post? Here’s a quiz!