Pull up a photo of any small airplane, like a Cessna, a Piper, a Diamond. Look at it for a moment. Now ask yourself: do you know what every single part does?

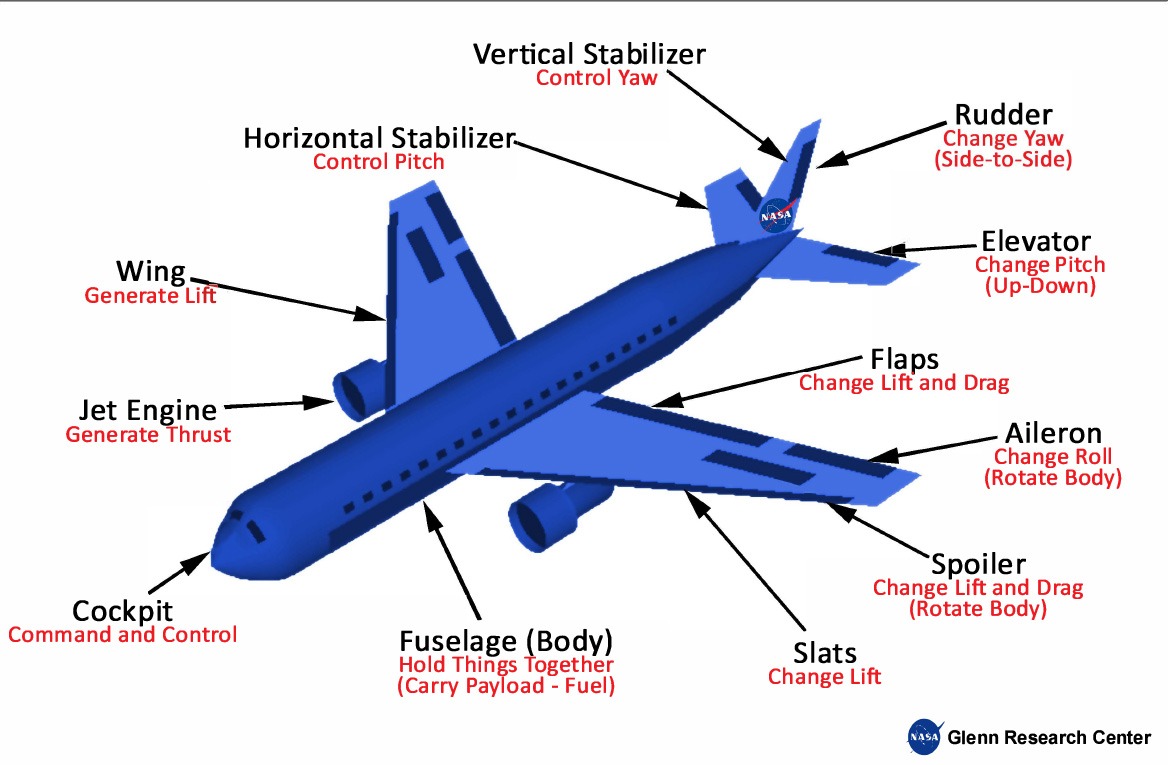

Most people can point to the wings and the engine. After that, it gets fuzzy fast. What’s that fin at the tail? Why does it need both a horizontal and a vertical piece back there? What are those little flap-like things on the wings? And what exactly is a fuselage, anyway? In the post on airfoils, we went deep on wing shape. Now let’s zoom out and look at the whole airplane. There is a purpose to every major component, what it does, and why removing or breaking any single piece would likely end your flight very quickly.

The Five Main Components

There are five main structural components of a typical airplane:

Fuselage. Wings. Empennage. Landing Gear. Powerplant.

Every airplane you’ll ever fly, regardless of if it’s a single-engine trainer or a regional jet, has all five. They work as a system. Change one, and you change how all the others perform.

The Fuselage: The Backbone of the Airplane

The word “fuselage” comes from the French fusélé, meaning spindle-shaped. That’s exactly what it is — a long, tapered tube that connects everything else and gives the airplane its basic shape.

The fuselage houses the cockpit, passengers, and cargo. It’s also the structural anchor point for the wings, empennage, and landing gear. Everything attaches to it. Everything loads into it. It needs to be strong, light, and aerodynamically smooth all at the same time.

Aircraft designers have used two main approaches to build fuselages over the years.

The truss structure is the older method. Think of it like a bridge. It’s a rigid framework of steel tubes or wooden beams welded or bolted together, then covered with fabric or sheet metal. Early airplanes like the Piper Cub used truss construction, and some still do. It’s simple, repairable in the field, and tough.

The semi-monocoque structure is what you find on most modern aircraft. Instead of relying on an internal frame, the strength comes from the outer skin itself and reinforced by internal frames called bulkheads, lengthwise members called longerons and stringers, and circular rings called formers. The skin carries the stress. It’s like an egg: the shell provides the strength, not an internal skeleton.

The Wings: Where the Magic Happens

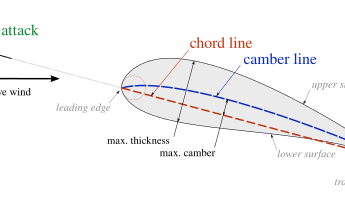

We covered airfoil shapes in detail in this post. Now let’s look at how a wing is actually built.

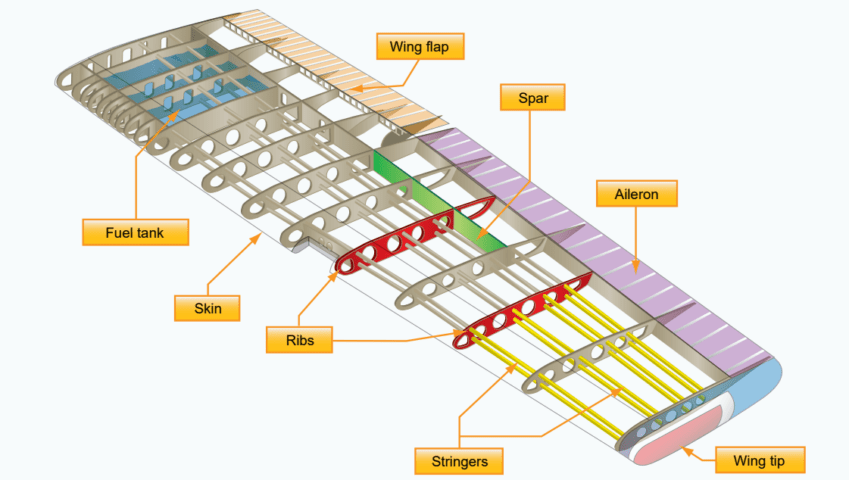

A wing isn’t hollow. It’s a carefully engineered structure designed to carry enormous loads. The key internal components are:

- Spars run spanwise (root to tip). They’re the primary load-bearing members, or the “bones” of the wing. Most wings have a forward spar and a rear spar that carry the bending forces created by lift.

- Ribs run chordwise (front to back), perpendicular to the spars. They give the wing its airfoil shape and distribute loads to the spars. Think of ribs as the ribs of an umbrella since they hold the shape.

- Stringers run spanwise between the ribs, stiffening the skin and helping transfer loads to the spars.

- Skin covers the whole structure. On modern aircraft, the skin isn’t just cosmetic. It carries a significant portion of the wing’s structural loads in what engineers call stressed skin design.

Wings also mount in different configurations. High-wing aircraft (like the Cessna 172) sit the wings on top of the fuselage. Low-wing aircraft (like the Piper Cherokee) mount them at the bottom. Each affects visibility, stability, and ground handling differently. Some wings use external struts for additional support (semi-cantilever), while others carry all their loads internally (full cantilever).

Control Surfaces on the Wing

The wings don’t just generate lift — they’re also home to several critical control surfaces.

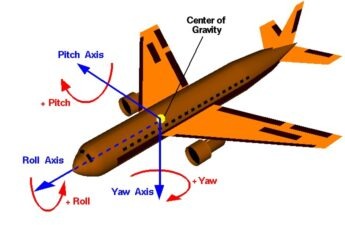

Ailerons sit at the outboard trailing edge of each wing. When you roll the control wheel, one aileron goes up while the other goes down. The wing with the down aileron generates more lift and rises; the wing with the up aileron drops. That’s how an airplane banks and turns.

Flaps occupy the inboard trailing edge. Unlike ailerons, both flaps move down together. Extending the flaps increases the wing’s camber, making it a higher-lift airfoil. This lets the airplane fly more slowly without stalling, which is exactly what you need during takeoff and landing.

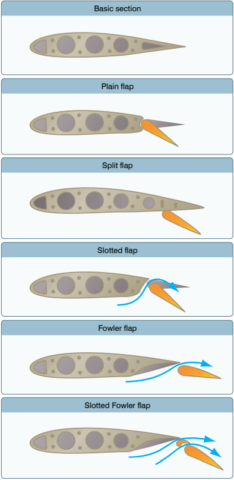

There are four common flap types: plain flaps (simply hinge down), split flaps (only the lower surface deflects), slotted flaps (a gap allows high-energy air to flow through and delay separation), and Fowler flaps (slide backward and down, increasing both camber and wing area). Fowler flaps are the most effective and appear on most larger aircraft.

The Empennage: The Tail That Keeps You Pointed Right

“Empennage” comes from the French empenner, which means to feather an arrow. (It rhymes with “fuselage”). Like the feathers on an arrow, the empennage keeps the airplane flying straight and controlled.

The empennage has two fixed surfaces and two (or more) movable ones:

- Vertical stabilizer: The upright fin that provides directional stability, keeping the nose from yawing randomly.

- Horizontal stabilizer: The small horizontal surface that provides pitch stability, keeping the nose from pitching uncontrollably.

- Rudder: Hinged to the vertical stabilizer and controlled by the pilot’s foot pedals. It controls yaw. The left pedal yaws left, right pedal yaws right.

- Elevator: Hinged to the horizontal stabilizer and controlled by the yoke or stick. Pull back and the nose rises; push forward and it drops.

- Stabilator: Found on some aircraft like the Piper Cherokee, this replaces the separate horizontal stabilizer and elevator with one pivoting unit. More effective, but requires careful design to avoid over-sensitivity.

Landing Gear: Bridging Air and Ground

The landing gear does one job: support the airplane on the ground without weighing it down too much in the air. Simple in concept, surprisingly complex in practice.

Tricycle gear (a nose wheel plus two main wheels) is the dominant configuration for modern aircraft. It’s forgiving, easy to taxi, and makes nose-overs on landing nearly impossible.

Conventional gear (also called tailwheel or “taildragger” configuration) uses two main wheels forward and a small wheel under the tail. It is harder to land, but the higher nose keeps the propeller clear of rough or unimproved strips. Landing gear can be fixed (always down) or retractable (folds away in flight). Retracting the gear dramatically reduces parasite drag. The difference in cruise speed between a fixed-gear and retractable-gear version of the same aircraft can be 20 to 30 knots.

The Powerplant: Turning Fuel Into Motion

The term powerplant covers everything involved in generating thrust — the engine, propeller, and all supporting systems.

Most small training aircraft use horizontally opposed piston engines. That is, four or six cylinders laid flat on opposite sides of a crankshaft. They’re compact, lightweight, and reliable. Common examples include the Lycoming O-320 in the Cessna 172 and the Continental O-300. The engine drives a propeller. As we covered in the post on why things fly, each propeller blade is an airfoil generating lift in the forward direction. The entire engine sits inside a removable shell called a cowling that streamlines airflow, reduces drag, and manages engine cooling temperature.

How It All Works Together

Here’s the key insight the FAA wants every pilot to internalize: these five components aren’t independent; they are a tightly coupled system.

The fuselage transfers loads from the wings to the landing gear on the ground, and from the powerplant to the empennage in the air. The wings generate lift but also create rolling moments that the ailerons must balance. The empennage provides stability that works against the wing’s tendency to pitch. The landing gear absorbs impact loads that can spike to several times the aircraft’s normal weight. Every time you do a preflight inspection, you’re evaluating this system. Even a small issue like a dent in the fuselage skin, a loose aileron hinge pin, or a flat tire on the main gear can cascade into a much bigger problem. Understanding the structure doesn’t just help you pass your written exam. It helps you understand what you’re looking for every single time you walk out to the flight line.

See how much you remember from this article with this fun quiz!